|

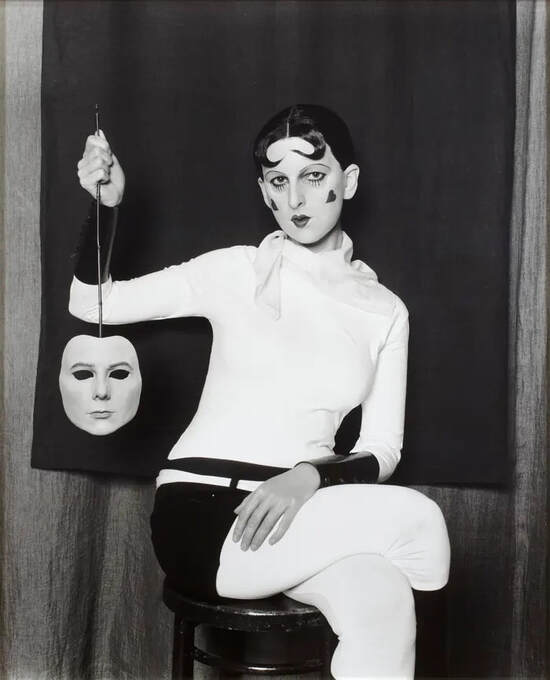

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky)American, 1890–1976 “I have finally freed myself from the sticky medium of paint, and am working directly with light itself.” 1 So enthused Man Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitzky) in 1922, shortly after his first experiments with camera-less photography. He remains well known for these images, commonly called photograms but which he dubbed “rayographs” in a punning combination of his own name and the word “photograph.” Man Ray’s artistic beginnings came some years earlier, in the Dada movement. Shaped by the trauma of World War I and the emergence of a modern media culture—epitomized by advancements in communication technologies like radio and cinema—Dada artists shared a profound disillusionment with traditional modes of art making and often turned instead to experimentations with chance and spontaneity. In The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows, Man Ray based the large, color-block composition on the random arrangement of scraps of colored paper scattered on the floor. The painting evinces a number of interests that the artist would carry into his photographic work: negative space and shadows; the partial surrender of compositional decisions to accident; and, in its precise, hard-edged application of unmodulated color, the removal of traces of the artist’s hand. In 1922, six months after he arrived in Paris from New York, Man Ray made his first rayographs. To make them, he placed objects, materials, and sometimes parts of his own or a model's body onto a sheet of photosensitized paper and exposed them to light, creating negative images. This process was not new—camera-less photographic images had been produced since the 1830s—and his experimentation with it roughly coincided with similar trials by Lázló Moholy-Nagy. But in his photograms, Man Ray embraced the possibilities for irrational combinations and chance arrangements of objects, emphasizing the abstraction of images made in this way. He published a selection of these rayographs—including one centered around a comb, another containing a spiral of cut paper, and a third with an architect’s French curve template on its side—in a portfolio titled Champs délicieux in December 1922, with an introduction written by the Dada leader Tristan Tzara. In 1923, with his film Le Retour à la raison (Return to Reason), he extended the rayograph technique to moving images. Around the same time, Man Ray’s experiments with photography carried him to the center of the emergent Surrealist movement in Paris. Led by André Breton, Surrealism sought to reveal the uncanny coursing beneath familiar appearances in daily life. Man Ray proved well suited to this in works like Anatomies, in which, through framing and angled light, he transformed a woman’s neck into an unfamiliar, phallic form. He contributed photographs to the three major Surrealist journals throughout the 1920s and 1930s, and also constructed Surrealist objects like Gift, in which he altered a domestic tool (an iron) into an instrument of potential violence, and Indestructible Object (or Object to Be Destroyed), a metronome with a photograph of an eye affixed to its swinging arm, which was destroyed and remade several times. Working across mediums and historical movements, Man Ray was an integral part of The Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition program early on. His photographs, paintings, drawings, sculptures, films, and even a chess set were included in three landmark early exhibitions: Cubism and Abstract Art (1936); Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism (1936–37), for which one of his rayographs served as the catalogue’s cover image; and Photography, 1839–1937 (1937). In 1941, the Museum expanded its collection of his work with a historic gift from James Thrall Soby, an author, collector, and critic (and MoMA trustee) who had, some eight years earlier, acquired an expansive group of Man Ray’s most important photographs directly from the artist. Within this group were 24 first-generation, direct, unique rayographs from the 1920s that speak to Man Ray’s ambition, as he wrote in 1921, to “make my photography automatic—to use my camera as I would a typewriter.” https://www.vintageannalsarchive.com/deep-dive---man-ray.html themstory: Claude Cahun Is the Gender-Nonconforming Anti-Fascist Hero We Deserve Although usually discussed as a lesbian, Cahun adamantly rejected gender. “Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation,” Cahun wrote in their autobiography, Disavowels. “Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” For this reason, I use gender-neutral pronouns in discussing Cahun. Born in 1894, Cahun came from an established family of Jewish writers in France. Today, Cahun is mostly remembered for their incredible self-portraits, which used fanciful homemade costumes and scenery to fashion new lives for them to try on. Wiry, with a shaved head and an intense gaze, Cahun slipped easily between genders and identities in their art. In one series, Cahun plays a dandy bodybuilder with spit curls on their forehead and hearts drawn on their cheeks. In another, an elaborate wig and heavy eye make-up leave Cahun looking like an extra from Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? In perhaps my favorite photo, Cahun pops the collar of a checkered jacket while looking away from a nearby mirror, simultaneously hiding and revealing the tender skin of their throat, in a pose that is both tough and vulnerable. The reason I find myself thinking about Claude Cahun today, however, is not their photography, but rather, their resistance to Nazi forces during World War II. During the war, Cahun and their life partner Marcel Moore (who was also Cahun’s step sister), lived on Jersey, one of an archipelago of islands that dot the English Channel off the coast of Normandy. When German forces conquered France and began using the island as a training ground for new recruits, Cahun and Moore waged a secret, two-person campaign of disinformation and morale-destruction, using a weapon the Nazis never expected: Surrealism. The pair’s antics would have been hysterical, if they hadn’t been so dangerous. They slipped anti-fascist poems into the pockets of soldiers as they walked past them on parade. Moore spoke fluent German, so they would write fake letters pretending to be disgruntled soldiers, urging the new recruits to desert. They stole propaganda posters and cut them up into resistance flyers, which they hid inside cigarette boxes and left around town for soldiers to find. By the time they were caught in 1944, the German forces were convinced that Jersey was home to a full-on resistance movement, never suspecting it was all the work of a pair of middle-aged, eccentric “sisters.” The Nazis sentenced Cahun and Moore to death. However, the island was liberated before the Germans were able to execute them. The two remained in Jersey for another decade, until Cahun died in 1954, never having fully recovered from the year they spent in a makeshift German prison. Their writing out of print, their photography completely forgotten, Cahun languished in virtual obscurity until French art historian Francois Leperlier brought them to public attention in the 1980s. Since then Cahun has become recognized as a Surrealist master, on par with photographer Man Ray. However, while their resistance to fascism is widely lauded, their resistance to traditional gender binaries is less recognized. Cahun is primarily seen as a lesbian icon, and rarely as a transgender one. I don’t wear Saints’ medals anymore, and haven’t lit a candle to one in decades. But if I were to maintain an altar, Claude Cahun would sit squarely at the center, the patron saint of surrealist Nazi fighters, the ancestor we all need today. Hugh Ryan is the author of the forthcoming book When Brooklyn Was Queer (St. Martin’s Press, March 2019), and co-curator of the upcoming exhibition On the (Queer) Waterfront at the Brooklyn Historical Society. https://www.them.us/story/themstory-claude-cahun Deep Dive - Ruth Gordon

Ruth Gordon was born in Wollaston, Massachusetts on October 30, 1896. Her mother was Annie Ziegler Tapley and her father, Clint Jones, was a ship’s captain turned factory foreman. In her autobiography, Gordon wrote, “I began working when I was nineteen. I come from hard-working people, it never occurred to me not to work. My father was a foreman of a food factory, he got thirty-seven dollars a week. Out of that he supported me, supported my mother, sent me to school, gave me four hundred dollars to be taught drama so I could go on the stage.” Gordon fell in love with theater while she was in high school. Her family shared the belief that acting for women was synonymous with promiscuity: “’My Aunt Ada told Mama, ‘For Ruth to go to be an actress is like being a harlot.’” But as Gordon herself put it, she was “a determined woman. I’ve had to fight for what I wanted all my life. Even as a child when everybody in the family was against my going on the stage, particularly my father, I battled vigorously till I wore them all down.” After graduating from high school, Gordon traveled to New York City, where she visited the offices of New York Theatre managers looking for work. Her father told her that “Any profession which didn’t offer me a berth at the end of six weeks . . . I would turn my back on.” After months of being told there was “nothing at present” by “Every kind of everybody’s office boy,” Gordon’s parents urged her to enroll in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where she was dropped after a single term “for not having what it took.” In 1917, Gordon began to appear in the silent films then being shot in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Her break came that same year, when she was cast as Nibs (one of the Lost Boys), in Peter Pan on Broadway, opposite Maude Adams. She worked steadily in theater for the remainder of her life. In addition to acting, Gordon authored numerous autobiographical writings, plays, and screenplays. Her second husband, Garson Kanin, observed, “looking at Ruth, it seems to me that her acting gains a good deal from her writing, and conversely her writing is stylish and lively because of her acting. For example, in her playwriting, she knows how, because she’s an actress, to write a speakable line. And because she writes, she has a sense and feeling about the written word which many actors lack.” Still, when Gordon wrote her first play, Years Ago, based on her memoir of the same title, people said “her husband wrote it for her and everyone says [George] Kaufman put in the funny lines.” In her autobiographical writings, Gordon spoke candidly about the challenges of working in theater during the first half of the twentieth century. Gordon recounted an audition in which the director told her to read from a script he had prepared for her alone: “ ‘We’ll read from this. Stand here.’ He pointed to a space beyond his desk. ‘It’s with your husband in Act One.’ He gently put his lips to mine. I had to have the part. ‘You’re sweet. Shall we begin?’ He leaned over and covered my mouth with his lips. His tongue went slowly in, out, in.” Gordon said that other women advised her to respond to such harassment by thinking about it in quid pro quo terms: “Make ’em think you’d go to bed with them, but! You will, but! And don’t lay down on the desk when the stenog goes home unless they sign a ten- year starring contract at umpteen dollars!” Gordon also wrote about what life was like for sexually active professional women in an era when both birth control and abortion were illegal. It was hard, she wrote, to figure out what to do when a woman got pregnant, especially for women who were on the road a great deal. In 1918, Gordon married actor Gregory Kelly, after co-starring with him in the play Seventeen. When she got pregnant the first time, Kelly “said hot baths might work and there was a drug named ergot. It needed a prescription, he got it. It didn’t work, just made me sick. https://www.vintageannalsarchive.com/deep-dive---ruth-gordon.html

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed