|

The relationship between artists and philosophers is not often a close or easy one. Some great artists developed philosophical theories to guide their practice. But when Piet Mondrian or Henri Matisse spelled out their aesthetic theorizing, one is aware that however important these ideas were for their art, it’s not easy to understand them as freestanding philosophical arguments. And, conversely, when even the most distinguished philosophers write about art, almost always their concerns are distant from those of practicing artists. Artists and philosophers usually have different skills — and both activities tend to be all-consuming.

When a teenager, Adrian Piper read a great deal of philosophy and contemporary fiction, listened to much avant-garde music, and became a passionate film connoisseur. After studying at the School of Visual Arts, she became a successful conceptual artist, exhibiting in major commercial New York galleries, starting when she was only 21. At this time, she worked as an artist’s model for Raphael Soyer. And, the very same year, when told by a friend that she should read Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, she embarked on studies that led to a PhD at Harvard University, writing her thesis with the best-known American social philosopher, John Rawls, , and traveling to Heidelberg, Germany, to study Kant. (In general, speaking myself as a philosopher, Kant’s first critique is one of our most challenging, and most commented on texts. Understanding Kant, it has rightly been said, is an IQ test for philosophers.) She then embarked on a teaching career that would lead to professorships at such major universities as University of Michigan, Georgetown, UC San Diego, and Wellesley. Piper describes herself as an artist and a philosopher. Many artists read some philosophy, and some philosophers look seriously at visual art. That said, I cannot think of anyone else, either a historical figure or some present-day person, who is both a major artist and also a practicing, skilled academic philosopher. What needs to be added is that, as she has said, Piper is an artist whose practice is informed by her professional skills as philosopher. In her philosophy lecture “The real thing strange” published in the catalogue of her recent retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, she speaks of her “project of directing you to that place in the mind where my art work lives and where you have to live and be comfortable, if you want to meet any contemporary artwork, including mine, on its own territory.” And she goes on to offer a lucid, highly subtle account of how to correctly understand contemporary art — an analysis that in some significant ways takes issue with Kant’s own account of aesthetic theory. Piper’s essay deserves close attention, for understanding its argument seems essential to any full evaluation of her art. Piper’s new memoir, Escape to Berlin (APRA Foundation, 2018), begins: Would you like to know why I left the U.S. and refuse to return? This is why. Piper tells the story of her childhood in Manhattan and her early education. “On my father’s strict orders, I was never hit or spanked or beaten or whipped.” And so, she explains, she “grew up physically inviolate, unable even to imagine the possibility of a breach to my physical integrity.” This experience carried over, she says, into her experience of philosophical argument, where she does not “back down […] unless you can show me a genuine flaw in my view.” Thanks to this early familial love, she became enviably self-confident. As she says: “I do not need your help. I was loved.” In college, she says, she “behaved uncontrollably […] raising my hand every five minutes in every class meeting to innocently request clarification […] dumfounding my instructors.” As she rightly notes, there are a number of students in philosophy like her, a “misguided troublemaker.” When I taught, I occasionally had students somewhat like her, who always were exciting and worth engaging in prolonged discussion in class and after. I remember one of my favorite students, who just wouldn’t shut up. I loved having her in the class, because she forced me to think hard. Is it surprising that now she’s a successful professor? Philosophers love to argue — it’s what we do. Rest of the article below... https://hyperallergic.com/470351/adrian-piper-escape-to-berlin-2018/

0 Comments

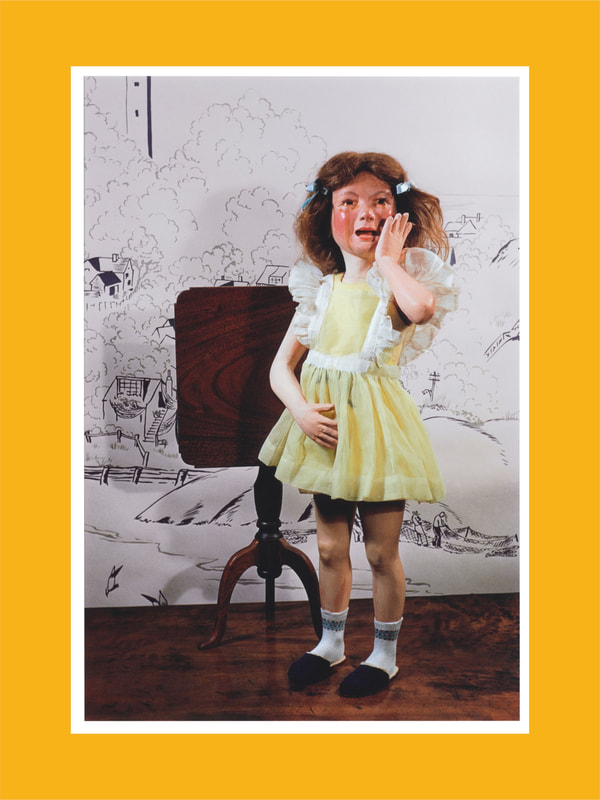

Meet Morton Bartlett, The Harvard Man Who Secretly Made Life-Size Dolls Most children own a doll of some kind. Maybe an action figure, a stuffed furry bear, a porcelain princess. Some of these dolls wind up on shelves like proto-works of art, but others remain close to their owners, serving in the roles of partner-in-crime, confidante, bedmate and best friend. The inanimate creatures come to life in the eyes of their guardians, taking on the personality traits, fantastical and ordinary, ascribed to them. There are three boy dolls in total; the rest are girls, approximately aged 8 to 16. Made with the help of both genders are dressed up in outfits expertly stitched and knitted. Their body parts are removable, so the dolls could change outfits without causing a mess. In spite of all this precision, though, Bartlett's dolls still look like dolls -- not people. What kind of a man would devote years of his life -- from 1936 to 1963, approximately one year per doll -- to such an uncanny passion? The answer, at least according to Bartlett, is a relatively conventional one. Bartlett was born in Chicago in 1909. He was orphaned at the age of 8, and adopted by a well-to-do family in Boston soon after. He received a top quality education, first at Phillips Exeter Academy and then at Harvard University for two years before dropping out. He worked some odd jobs -- gas station attendant, furniture salesman -- before settling into a career in graphic design and commercial photography. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/morton-bartlett-doll-photos_n_563295efe4b063179911ce33/amp If you’ve ever re-watched Disney’s The Little Mermaid as an adult, you’ve probably had that feeling that the movie’s villain, Ursula The Sea Witch, reminds you of someone. As it turns out, that’s not a coincidence. Ursula is inspired, in both appearance and demeanor, by drag legend and John Waters muse Divine. This revelation begs the question, how does a character based on a poo-eating, ultra-profane cult movie star wind up in a Disney movie? The missing link, according to a new article in Hazlitt, was Howard Ashman. Ashman was the playwright and lyricist responsible for Little Shop Of Horrors. He also came up in the same Baltimore-D.C. gay scene as Divine. After the failure of Smile, his post-Little Shop broadway debut, Ashman and his writing partner decided to take a job with Disney. Depressed and dejected, he and Menken accepted an offer from Disney executives Jeffrey Katzenberg and Michael Eisner to move across the country and write the lyrics for an animated feature. The studio was reeling from its own expensive bomb. With a budget of $45 million in 1985, The Black Cauldronwas one of the most ambitious animated films that had ever been made. It earned only $23 million at the box office. Bringing Ashman and Menken to work on an adaptation of The Little Mermaid felt like the studio’s last chance at a blockbuster. Ashman saw that animated films could be like musicals—with songs furthering the plot rather than just adding color. In working on the film he drew on his Children’s Theater training and his West Village attitude. Early on, The Little Mermaid’s directors and animators created several iterations of Ursula. One was a manta ray inspired by Joan Collins. Another was a “beautiful but deadly” scorpion fish, recalled director John Musker. None worked, until an animator named Rob Minkoff drew a vampy overweight matron who everyone agreed looked a lot like Divine. She had the eye makeup, the jewelry, the body type, and the glamour. But instead of tentacles, Minkoff gave her a shark tail and a pink Mohawk. The sketches were almost there. Musker, Disney executive Jeffrey Katzenburg, and Ashman could all feel it.https://www.avclub.com/read-this-how-divine-inspired-ursula-the-sea-witch-1798243255 Ladies Tea Party: Amazing Photos of Female Punk Icons Gathering Together at a London Hotel in August, 1980 In 1980, during a tour with Blondie, Debbie Harry hosted a tea party at a London hotel, gathering together many of the women prominent in music at the time. Chrissie Hynde was there; Siouxsie Sioux; the Slits guitarist Viv Albertine; Pauline Black from The Selecter; and Poly Styrene from X-Ray Spex. It looks as though there was a lot of laughter. This was a different time for women in music. Two years earlier Kate Bush, who was invited to tea but didn’t make it, had become the first female solo performer to reach number one in the British charts with her own song (Wuthering Heights). There was a widespread assumption that there was room for just one main female performer in each genre. If another appeared, they were expected to battle it out for the title of queen of pop/soul/disco/punk. Harry was keen to cut through that. “I really wanted to get together with all the punk females for an afternoon of celebration,” she explained. “It’s a great memory.” If you did that today, I say, you would need more than a hotel room. “I would need a hall!” she says, laughing. “It has changed a lot. It’s really grown, hasn’t it?” (Photos by Michael Putland/ Chris Stein/ Getty Images) https://www.vintag.es/2018/10/ladies-tea-party-1980.html If you had lived in 1920s Paris, you would know who Barbette was. She was an icon of the night. A muse to the greats. A pioneer of queer. She might have built a career as a trapeze and high-rope performer in the United States, but made a name for themself in a very different milieu. As a “female impersonator”, Barbette captured the photographic eye of Man Ray and the literary eye of Jean Cocteau, and at the height of fame, would even go on to coach Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis with their career-defining roles in Some Like it Hot. Vander Clyde Broadway (a disputed last name), was born in Texas and attended a circus in Austin as a young boy, fascinated by the high-wire act. He would practice by walking across his mom’s steel clothing lines. As Barbette later told the New Yorker in a fantastic 1969 profile, “I knew I’d be a performer, and from then on I’d work in the fields during the cotton-picking season to earn money in order to go to the circus as often as possible.”

Broadway responded to a billboard ad looking for a replacement in the famed Alfaretta Sisters act. They asked Broadway if he would mind wearing women’s clothing, as “the plunging and gyrating are more dramatic in a woman” and he readily agreed. In the new role, Broadway went on to be part of Erford’s Whirling Sensation, performing a stunt in which the performer hung by his teeth wearing large butterfly wings. (Barbette would later become known for a signature ballgown and ostrich-feather hat.) The Texan began developing a unique act, inspired by the magic not only of these death-defying feats but also of disguising his gender, only revealing he was a man at the end, taking off his wig and parading around with a masculine gait. As he told the New Yorker, “I’d always read a lot of Shakespeare and thinking that those marvelous heroines of his were played by men and boys made me feel that I could turn my specialty into something unique.” Broadway’s popularity as Barbette, a name he felt wouldn’t be too alienating for American audiences, led the way to Europe, where she became a sensation. In the fall of 1923, Barbette fell in love with Paris and Paris fell in love with Barbette. She became a regular feature at the Moulin Rouge and was quickly taken in by connected American expats, who introduced them to their circle of Parisian creative types, including Jean Cocteau, who was a fan of the circus and vaudeville. In a letter to friends, Cocteau described Barbette’s performance as a “theatrical masterpiece. An angel, a flower, a bird.” In 1926, Cocteau wrote an influential essay on Barbette in the literary magazine Nouveau Revue Française entitled “Le Numéro Barbette,” describing what made the performer so enthralling: “The reason for Barbette’s success is that he appeals to the instincts of several audiences in one room and mysteriously brings together contradictory opinions. For he is liked by those who see him as a woman and by those who sense the man in him — not to mention those stirred by the supernatural sex of beauty.” In a very French analysis, Cocteau argued that Barbette had transcended, both figuratively and literary, what could have simply been a gimmick done in bad taste: “He walked tightrope high above the audience without falling, above incongruity, death, bad taste, indecency, indignation.” Rest of Article below... https://www.messynessychic.com/2023/02/15/who-was-the-1920s-moulin-rouge-drag-queen-that-inspired-man-ray-and-cocteau/ Ep 22: Lennon Parham (Focus on Comedy)

I’ve seen Lennon in a bunch of stuff over the years and always loved their work, but there was something in "Minx" to me that transcended her in my opinion to the level of comic genius and genius performer. She embedded her character Shelly with pure authenticity, compassion, and true kindness, that almost came through the screen. These real life qualities also became very clear while speaking with her. This episode focuses primarily on "Minx" but also digs into her days at UCB, being interviewed by Joan Rivers, working on Veep, Lady Dynamite, and more. I was also super impressed by the way she does her research and creates characters from real life experiences. Her work is definitely worth exploring, and please keep an eye on her future work as an actor, creator, and a director. She will only continue to do amazing work! Lastly, and most importantly, she tells the amazing story of making her insane fantasy scene in season one of "Minx". It involves making out with twin priests and the pope, and also features a horse! It's amazing! https://anchor.fm/vaapod The Muppets were never meant to be a kids show. The original pilot was called The Muppet Show: Sex and Violence (TV Special 1975)

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed